For those unfamiliar with what a mutual fund wholesaler is, allow me to provide a brief explanation. Asset management companies, who manufacture mutual funds and other investment related products, employ legions of wholesalers to go out in to their geographic territories to educate investment professionals, like me, in hopes that they will sell their products to their clients.

A good wholesaler will do whatever it takes to make it on an advisor’s calendar including, but not limited to, visiting you in your office, taking you out to lunch or inviting you to an educational event at an intriguing venue to hear from a prominent portfolio manager, analyst or economist.

With the exception of a few people I truly consider my friends, I seldom take as much as phone call, let alone a lunch appointment with a wholesaler. They aren’t bad people or anything, it’s just that I don’t want to be disingenuous when I have no expectation of doing any business. I rather reach out to them should I have questions on a particular product.

Now, wholesalers don’t want advisors selling just any old fund to their clients. No. They prefer that advisors sell actively managed funds because that’s where the money is made. For example, the cost of your average large-cap mutual fund is about 1.0%/year, which is about 0.85%/year higher than your average S&P 500 index fund.

Therefore, it would make complete sense to tie a wholesaler’s compensation to annual sales goals based primarily on the sale of actively managed mutual funds. But let’s not forget that asset management companies also have to cut big checks to their portfolio managers. Managers who attempt to do something very difficult—beat the market.

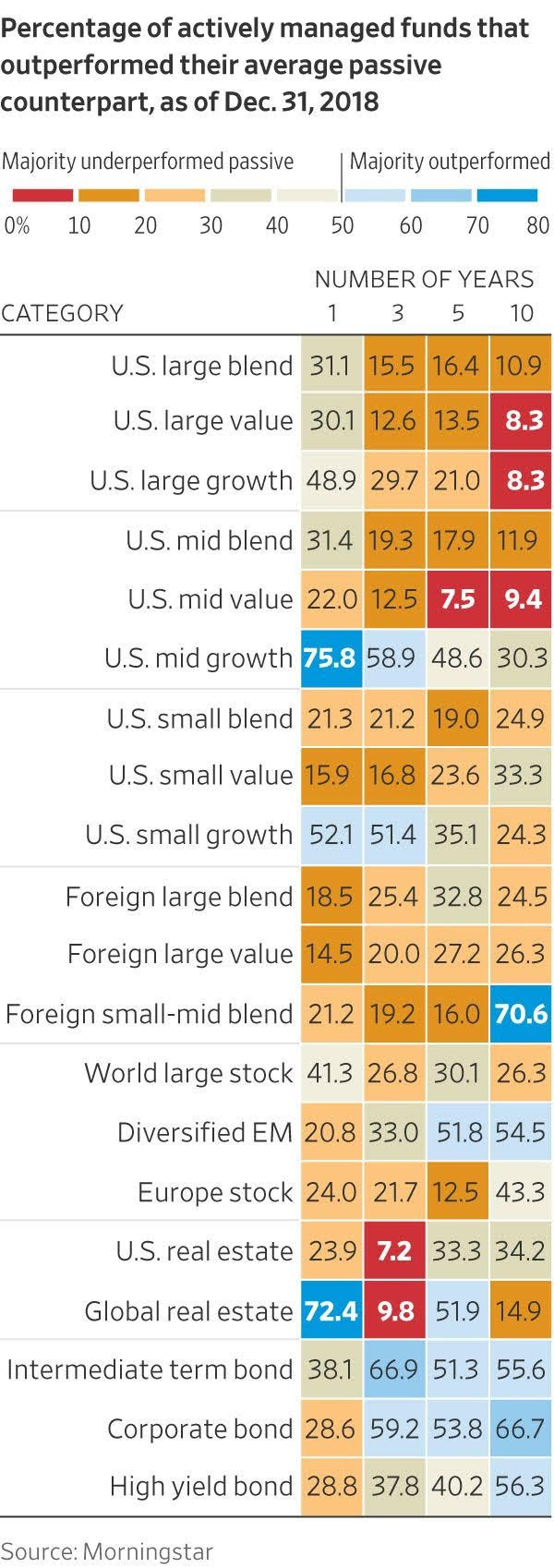

The table above shows the percentage of active managers that actually outperform their respective asset class on a trailing 1, 3, 5 and 10 years. As you can see, most managers can’t beat the market, but that won’t stop them from trying as the lion’s share of investible assets remain in actively managed products.

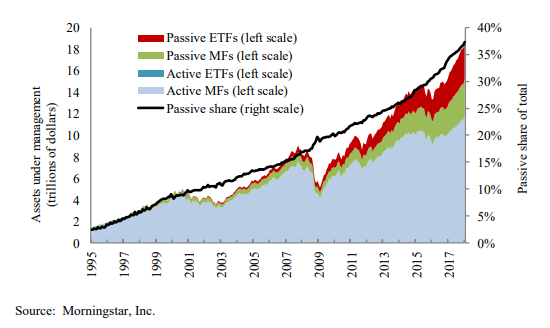

When I moved to New York City in 2008, passive investments made up slightly less than 20% of all U.S. mutual fund and ETF assets, up from 3% in 1995. Today, passive funds account for approximately 37% of combined U.S. mutual funds and ETF assets, according to Morningstar.

As the chart above illustrates that, no matter which side of the active vs. passive management debate you take, you can’t ignore the direction we’re heading in. While I professionally use both passive and active funds, I fully believe it’s only a matter of time before passive investing dominates active investing as flows out of active continue to accelerate.

Which brings me back to the wholesaler. What will they do in a passive investment dominated future? Some firms are already adapting at the product level by offering both active and passive products, but if fund expense is any indication of how money flows from products to people than there is roughly six times as much cause for them to be worried.

Ironically, these challenges mirror that of the financial advisor (or in this case the glorified broker) who has yet to recognize that their value has shifted away from investments and towards financial planning, advice and service. Wholesalers, like advisors who lead with asset management, need to do more than serve up good a story surrounding a particular mutual fund.

For example, rather than tell me how one of your portfolio managers beat their benchmark that one time, please show me an unconventional marketing idea that has worked wonders for another advisor. Don’t give me a fund fact sheet but please provide me with access to your firm’s talent and data so that I can create amazing content of my own. While you’re at it, please share your own creative ideas with me. Let’s collaborate.

How this all get tied into their compensation is a little tricky because, unlike tracking mutual fund purchases, measuring the impact from these support activities isn’t as easy to quantify. Perhaps then, phasing out sales goals all together will be the way to go. I know that might not be the perfect solution, but I’m sure it’s not the only one.

The moral of the story is that when the value proposition shifts, trouble follows only if the organization getting disrupted fails to follow where the value is going. While this might require substantial changes in the short term, such as offering new products, providing different types of service and modifying compensation structures, it means the organization will stand to generate value in the long term.

What did you have to say about it?

Name me something harder than beating the stock market.

— Douglas A. Boneparth (@dougboneparth) February 6, 2019